- Hardware networks send packets of data having a specified format.

- The software Internet is no different. It needs virtual packets.

- Packets have a header of specified form, which is overhead,

and a payload.

Header Payload - Payload is 1 to 64k bytes in length, more practical than hardware.

- Current practice is to avoid payloads more than a K or two.

- Packets have a header of specified form, which is overhead,

and a payload.

- IP4 Header format:

VersionH. LenServiceTotal LengthIdentificationFlagsFragment OffsetTTLTypeHeader ChecksumSource IP4 AddressDestination IP4 AddressOptions, if any08162431

- Version: The IP version, 4.

- H. Len: The header length, in words. Needed since the options field can vary in size.

- Service: A routing priority whose use has evolved. We'll ignore it for now.

- Total Length: Length of the whole packet, in bytes.

- Identification, Flags and Fragment offset. These are used with fragmentation, which is discussed later. When sending a packet, the Identification field is a random number that changes with each packet sent, and the others are zero.

- TTL = Time To Live. A packet is dropped after being routed this many times. This prevents a routing loop from keeping packets on the net forever. (A routing loop should not occur, but we don't want to make things worse if it does.)

- Type: The type of data in the payload. This tells the receiver how to process the arriving data.

- Header Checksum: Just that. Packets with a bad header checksum are dropped.

- Source and destination addresses. The 32-bit IP4 addresses where the packet came from and is going to.

- Options. Not often used. If options are present, the section is padded to a multiple of 32 bits.

- IP6 header.

- IP4 uses the same header for all packets, which can cause some

waste. IP6 uses a more flexible format:

Base Header Extension 1 . . . Extension N - The base header appears on all packets, and extensions (if any) allow additional data. (Not likely to get away with none.)

- IP6 base header:

VersionTraffic ClassFlow LabelPayload LengthNext HeaderHop LimitSource IP6 Address

(4 rows)Destination IP6 Address

(4 rows)08162431- Version: The IP version, 6.

- Traffic class: Similar to IP4 service.

- Flow label: Identifies packets as belonging together. For instance, all the packets in a connection might have the same flow label. Has a number of advantages for routing, and IP4 hasn't got one.

- Payload length: Just that, in bytes.

- Next header: Tells what comes after, either an extension header type or a payload type.

- Hop Limit: Same as IP4 TTL.

- The source and destination addresses, which are 128 bits each, so they cover four lines in the diagram.

- Extension headers.

- Full implementations must support (though not always use) the

following headers:

- Hop-by-Hop Options

- Routing

- Fragment

- Destination Options

- Authentication Encapsulating

- Security Payload

- Hop-by-hop, if present must come first. It is the only one read by routers along the way. Others are processed only by the recipient.

- Full implementations must support (though not always use) the

following headers:

- IP4 uses the same header for all packets, which can cause some

waste. IP6 uses a more flexible format:

- Encapsulation.

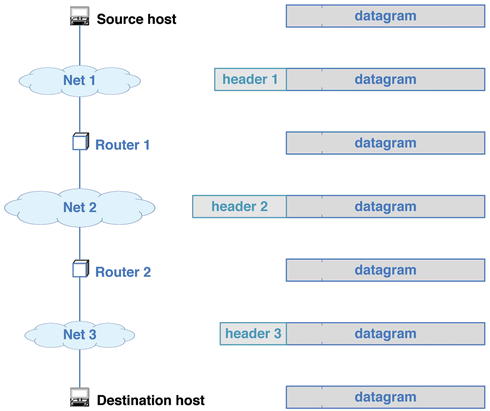

- Since IP is a software protocol, there are IP hardware packets.

- IP packets are carried as the payload of an underlying hardware.

IP HeaderIP PayloadFrame HeaderFrame Payload (IP datagram)

- If the underlying network is Ethernet, the frame header Frame Type field is hex 0800, for Internet.

- When the IP Datagram travels through the Internet, it must pass from one

hardware net to another.

- When flies through a router, it changes planes.

- Fragmentation.

- Each hardware limits its packet size, called a maximum Transmission Unit (MTU).

- For instance, and Ethernet frame carries 46-1500 bytes of payload.

- An IP datagram can have up to 64k, which doesn't fit too well.

- In that case, the datagram must be fragmented into smaller messages.

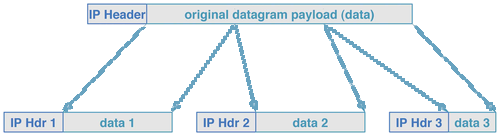

- IP4 Fragmentation

Each fragment carries a copy of the original header, with

changes.

Each fragment carries a copy of the original header, with

changes.

- The fragment offset field is set to the position in the original payload of the first byte in the fragment. Units of eight bytes.

- The fragment flag (in the flags field) is set to 1, on all fragments but the last.

- The identification is not changed, so all the fragments have the same id, which is is different from other packets.

- A datagram is a fragment if either its fragment bit is set, or its fragment offset is nonzero. The one without the flag set is the last one.

- Any router will fragment any IP4 datagram that won't fit on the outbound net.

- The datagram is reconstructed at the final destination.

- When the first fragment of a datagram arrives, the receiver starts a timer.

- It adds each additional fragment as it arrives.

- If the timer expires before they all arrive, the datagram is discarded.

- There is also a do-not-fragment flag. If set by the sender, the datagram is discarded if it ever needs to fragmented.

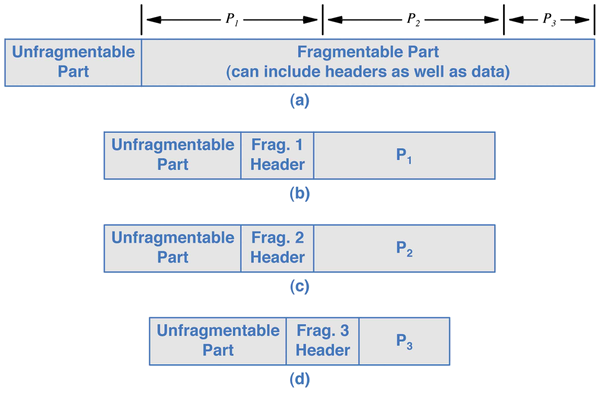

- Fragmentation in IP4 versus IP6.

- In IP4, each datagram has space for the fragment information (identifier, flag and offset). In IP6, the fragment extension header is added to fragments, and it holds the id and offset.

- The presence of the fragment header serves as the fragment flag.

- The unfragmentable part is the base header, plus any extension that must be read by routers. It is copied to each fragment.

- In IP4, datagrams are fragmented by routers as needed, but in IP6, a datagram must be fragmented by the sender. Routers do not do so.

- How does IP6 know to fragment?

- To know if a datagram must be fragmented, the sender must know the smallest MTU of any network along the path. This is known as the path MTU.

- This can be discovered by sending packets of various sizes, and seeing which get through.

- Routers will usually send an ICMP error message (covered later) when it must drop a packet for size, so the sender can tell which ones make it.

- This formalizes a practice used in IP4, where TCP senders will find the path MTU to avoid the inefficiency of fragmentation. The MTU can be found in IP4 by sending packets with don't fragment sent.